Here are two papers that may be useful for researchers in psychology, linguistics, and cognitive science:

Shravan Vasishth and Bruno Nicenboim. Statistical methods for linguistic research: Foundational Ideas - Part I. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2016. In Press.

PDF: http://bit.ly/VasNicPart1

Code: http://bit.ly/VasNicPart1Code

Bruno Nicenboim and Shravan Vasishth. Statistical methods for linguistics research: Foundational Ideas - Part II. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2016. In Press.

PDF: http://bit.ly/NicVasPart2

Code: http://bit.ly/NicVasPart2Code

This blog is a repository of cool things relating to statistical computing, simulation and stochastic modeling.

Search

Tuesday, August 02, 2016

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

A simple proof that the p-value distribution is uniform when the null hypothesis is true

[Scroll to graphic below if math doesn't render for you]

Thanks to Mark Andrews for correcting some crucial typos (I hope I got it right this time!).

Thanks also to Andrew Gelman for pointing out that the proof below holds only when the null hypothesis is a point null $H_0: \mu = 0$, and the dependent measure is continuous, such as reading time in milliseconds, or EEG responses.

Someone asked this question in my linear modeling class: why is it that the p-value has a uniform distribution when the null hypothesis is true? The proof is remarkably simple (and is called the probability integral transform).

First, notice that when a random variable Z comes from a $Uniform(0,1)$ distribution, then the probability that $Z$ is less than (or equal to) some value $z$ is exactly $z$: $P(Z\leq z)=z$.

Next, we prove the following proposition:

Proposition:

If a random variable $Z=F(T)$, then $Z \sim Uniform(0,1)$.

Note here that the p-value is a random variable, call it $Z$. The p-value is computed by calculating the probability of seeing a t-statistic or something more extreme under the null hypothesis. The t-statistic comes from a random variable $T$ that is a transformation of the random variable $\bar{X}$: $T=(\bar{X}-\mu)/(\sigma/\sqrt{n})$. This random variable T has a CDF $F$.

So, if we can prove the above proposition, we have shown that the p-value's distribution under the null hypothesis is $Uniform(0,1)$.

Proof:

Let $Z=F(T)$.

$P(Z\leq z) = P(F(T)\leq z) = P(F^{-1} F(T) \leq F^{-1}(z) )

= P(T \leq F^{-1} (z) )

= F(F^{-1}(z))= z$.

Since $P(Z\leq z)=z$, Z is uniformly distributed, that is, Uniform(0,1).

A screengrab in case the above doesn't render:

Thanks to Mark Andrews for correcting some crucial typos (I hope I got it right this time!).

Thanks also to Andrew Gelman for pointing out that the proof below holds only when the null hypothesis is a point null $H_0: \mu = 0$, and the dependent measure is continuous, such as reading time in milliseconds, or EEG responses.

Someone asked this question in my linear modeling class: why is it that the p-value has a uniform distribution when the null hypothesis is true? The proof is remarkably simple (and is called the probability integral transform).

First, notice that when a random variable Z comes from a $Uniform(0,1)$ distribution, then the probability that $Z$ is less than (or equal to) some value $z$ is exactly $z$: $P(Z\leq z)=z$.

Next, we prove the following proposition:

Proposition:

If a random variable $Z=F(T)$, then $Z \sim Uniform(0,1)$.

Note here that the p-value is a random variable, call it $Z$. The p-value is computed by calculating the probability of seeing a t-statistic or something more extreme under the null hypothesis. The t-statistic comes from a random variable $T$ that is a transformation of the random variable $\bar{X}$: $T=(\bar{X}-\mu)/(\sigma/\sqrt{n})$. This random variable T has a CDF $F$.

So, if we can prove the above proposition, we have shown that the p-value's distribution under the null hypothesis is $Uniform(0,1)$.

Proof:

Let $Z=F(T)$.

$P(Z\leq z) = P(F(T)\leq z) = P(F^{-1} F(T) \leq F^{-1}(z) )

= P(T \leq F^{-1} (z) )

= F(F^{-1}(z))= z$.

Since $P(Z\leq z)=z$, Z is uniformly distributed, that is, Uniform(0,1).

A screengrab in case the above doesn't render:

Sunday, January 17, 2016

Automating R exercises and exams using the exams package

It's a pain to design statistics exercises each semester, and because students from previous share old exercises with the new incoming students, it's hard to design simple exercises that students haven't already seen the answers to. On top of that, some students try to cheat during the exam by looking over the shoulder of their neighbors. Homework exercises almost always involve collaboration even if you prohibit it.

It turns out that you can automate the generation of fixed-format exercises (with different numerical answers being required each time). You can also randomly select questions from a question bank you create yourself. And you can even create a unique question paper for each student in an exam, to make cheating between neighbors essentially impossible (even if they copy the correct answer to question 2 from a neighbor, they end up answering the wrong question on their own paper).

All this magic is made possible by the exams package in R. The documentation is of course comprehensive and there is a journal article explaining everything:

Here is a quick example to get people started on designing their own customized, automated exams. In my example below, there are several files you need.

1. The template files for your exam (what your exam or homework sheet will look like), and the solutions file. I provide two example files: test.tex and solutiontest.tex

2. The exercises or exam questions themselves: I provide two as examples. The first file is called pnorm1.Rnw. It's an Sweave file, and it contains the code for generating a random problem and for generating its solution. The code should be self-explanatory. The second file is called sesamplesize1multiplechoice.Rnw and has a multiple choice question.

3. The exam generating R code file: The code is commented and self-explanatory. It will generate the exercises, randomize the order of presentation (if there are two or more exercises), and generate a solutions file. The output will be a single or multiple exam papers (depending on how many versions you wanted generated), and the solutions file(s). Notice the cool thing that even in my example, with only one question, the two versions of the exams have different numbers, so two people cannot collaborate and consult each other and just write down one answer. Each student could in principle be given a unique set of exercises, although it would be a lot of work to grade it if you do it manually.

Here is the exam generating code:

Save from the gists given above (a) the test.tex and solutiontest.tex files, (b) the Rnw files containing the exercise (pnorm1.Rnw, and sesamplesize1multiplechoice.Rnw), and (c) the exam generating code (ExampleExamCode.R). Put all of these into your working directory, say ExampleExam. Then run the R code, and be amazed.

If something is broken in my example, please let me know.

Shuffling questions: If you want to reorder the questions in each run of the R code, just change myexamlist to sample(myexamlist) in the call below that appears in the file ExampleExamCode.R:

It turns out that you can automate the generation of fixed-format exercises (with different numerical answers being required each time). You can also randomly select questions from a question bank you create yourself. And you can even create a unique question paper for each student in an exam, to make cheating between neighbors essentially impossible (even if they copy the correct answer to question 2 from a neighbor, they end up answering the wrong question on their own paper).

All this magic is made possible by the exams package in R. The documentation is of course comprehensive and there is a journal article explaining everything:

Achim Zeileis, Nikolaus Umlauf, Friedrich Leisch (2014). Flexible Generation of E-Learning Exams in R: Moodle Quizzes, OLAT Assessments, and Beyond. Journal of Statistical Software 58(1), 1-36. URL http://www.jstatsoft.org/v58/i01/.I also use this package to deliver auto-graded exercises to students over datacamp.com. See here for the course I teach, and here for the datacamp exercises.

Here is a quick example to get people started on designing their own customized, automated exams. In my example below, there are several files you need.

1. The template files for your exam (what your exam or homework sheet will look like), and the solutions file. I provide two example files: test.tex and solutiontest.tex

2. The exercises or exam questions themselves: I provide two as examples. The first file is called pnorm1.Rnw. It's an Sweave file, and it contains the code for generating a random problem and for generating its solution. The code should be self-explanatory. The second file is called sesamplesize1multiplechoice.Rnw and has a multiple choice question.

3. The exam generating R code file: The code is commented and self-explanatory. It will generate the exercises, randomize the order of presentation (if there are two or more exercises), and generate a solutions file. The output will be a single or multiple exam papers (depending on how many versions you wanted generated), and the solutions file(s). Notice the cool thing that even in my example, with only one question, the two versions of the exams have different numbers, so two people cannot collaborate and consult each other and just write down one answer. Each student could in principle be given a unique set of exercises, although it would be a lot of work to grade it if you do it manually.

Here is the exam generating code:

Save from the gists given above (a) the test.tex and solutiontest.tex files, (b) the Rnw files containing the exercise (pnorm1.Rnw, and sesamplesize1multiplechoice.Rnw), and (c) the exam generating code (ExampleExamCode.R). Put all of these into your working directory, say ExampleExam. Then run the R code, and be amazed.

If something is broken in my example, please let me know.

Shuffling questions: If you want to reorder the questions in each run of the R code, just change myexamlist to sample(myexamlist) in the call below that appears in the file ExampleExamCode.R:

sol <- exams(sample(myexamlist), n = num.versions,

dir = odir, template = c("test", "solutiontest"),

nsamp=1,

header = list(ID = getID, Date = Sys.Date()))

Wednesday, January 06, 2016

My MSc thesis: A meta-analysis of relative clause processing in Mandarin Chinese using bias modelling

Here is my MSc thesis, which was submitted to the University of Sheffield in September 2015.

The pdf is here.

Title: A Meta-analysis of Relative Clause Processing in Mandarin Chinese using Bias Modelling

Abstract

The reading difficulty associated with Chinese relative clauses presents an important empirical problem for psycholinguistic research on sentence comprehension processes. Some studies show that object relatives are easier to process than subject relatives, while others show the opposite pattern. If Chinese has an object relative advantage, this has important implications for theories of reading comprehension. In order to clarify the facts about Chinese, we carried out a Bayesian random-effects meta-analysis using 15 published studies; this analysis showed that the posterior probability of a subject relative advantage is approximately $0.77$ (mean $16$, 95% credible intervals $-29$ and $61$ ms). Because the studies had significant biases, it is possible that they may have confounded the results. Bias modelling is a potentially important tool in such situations because it uses expert opinion to incorporate the biases in the model. As a proof of concept, we first identified biases in five of the fifteen studies, and elicited priors on these using the SHELF framework. Then we fitted a random-effects meta-analysis, including priors on biases. This analysis showed a stronger posterior probability ($0.96$) of a subject relative advantage compared to the standard random-effects meta-analysis (mean $33$, credible intervals $-4$ and $71$).

The pdf is here.

Title: A Meta-analysis of Relative Clause Processing in Mandarin Chinese using Bias Modelling

Abstract

The reading difficulty associated with Chinese relative clauses presents an important empirical problem for psycholinguistic research on sentence comprehension processes. Some studies show that object relatives are easier to process than subject relatives, while others show the opposite pattern. If Chinese has an object relative advantage, this has important implications for theories of reading comprehension. In order to clarify the facts about Chinese, we carried out a Bayesian random-effects meta-analysis using 15 published studies; this analysis showed that the posterior probability of a subject relative advantage is approximately $0.77$ (mean $16$, 95% credible intervals $-29$ and $61$ ms). Because the studies had significant biases, it is possible that they may have confounded the results. Bias modelling is a potentially important tool in such situations because it uses expert opinion to incorporate the biases in the model. As a proof of concept, we first identified biases in five of the fifteen studies, and elicited priors on these using the SHELF framework. Then we fitted a random-effects meta-analysis, including priors on biases. This analysis showed a stronger posterior probability ($0.96$) of a subject relative advantage compared to the standard random-effects meta-analysis (mean $33$, credible intervals $-4$ and $71$).

Saturday, December 19, 2015

Best statistics-related comment ever from a reviewer

This is the most interesting comment I have ever received from CUNY conference reviewing. It nicely illustrates the state of our understanding of statistical theory in psycholinguistics:

"I had no idea how many subjects each study used. Were just one or two people

used? ... Generally, I wasn't given enough data to determine my confidence in the provided t-values (which depends on the degrees of freedom involved)."

"I had no idea how many subjects each study used. Were just one or two people

used? ... Generally, I wasn't given enough data to determine my confidence in the provided t-values (which depends on the degrees of freedom involved)."

Thursday, August 27, 2015

Five thirty-eight provides a brand new definition of the p-value

The Five-Thirty Eight blog provides a brand new definition of the p-value:

http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/psychology-is-starting-to-deal-with-its-replication-problem/?ex_cid=538twitter

"A p-value is simply the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as the one you saw if your hypothesis is false."

I thought this blog was run by Nate Silver, a statistician?

http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/psychology-is-starting-to-deal-with-its-replication-problem/?ex_cid=538twitter

"A p-value is simply the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as the one you saw if your hypothesis is false."

I thought this blog was run by Nate Silver, a statistician?

Observed vs True Statistical Power, and the power inflation index

People (including me) routinely estimate statistical power for future studies using a pilot study's data or a previously published study's data (or perhaps using the predictions from a computational model, such as Engelmann et al 2015).

Indeed, the author of the Replicability Index has been using observed power to determine the replicability of journal articles. His observed power estimates are HUGE (in the range of 0.75) and seem totally implausible to me, given the fact that I can hardly ever replicate my studies.

This got me thinking: Gelman and Carlin have shown that when power is low, Type M error will be high. That is, the observed effects will tend to be highly exaggerated. The issue with Type M error is easy to visualize.

Suppose that a particular study has standard error 46, and sample size 37; this implies that standard deviation is $46\times \sqrt{37}= 279$. These are representative numbers from psycholinguistic studies. Suppose also that we know that the true effect (the absolute value, say on the millisecond scale for a reading study---thanks to Fred Hasselman) is D=15. Then, we can compute Type S and Type M errors for replications of this particular study by repeatedly sampling from the true distribution.

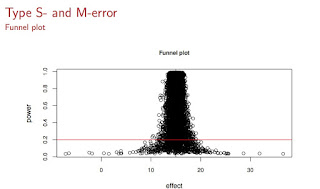

We can visualize the exaggerated effects under low power as follows (see below): On the x-axis you see the effect magnitudes, and on the y-axis is power. The red line is the power line of 0.20, which based on my own attempts at replicating my own studies (and mostly failing), I estimate to be an upper bound of the power of experiments in psycholinguistics (this is an upper bound, I think a more common value will be closer to 0.05). All those dots below the red line are exaggerated estimates in a low power situation, and if you were to use any of those points to estimate observed power, you would get a wildly optimistic power estimate which has no bearing with reality.

What does this fact about Type M error imply for Replicability Index's calculations? It implies that if power is in fact very low, and if journals are publishing larger-than-true effect sizes (and we know that they have an incentive to do so, because editors and reviewers mistakenly think that lower p-values, i.e., bigger absolute t-values, give stronger evidence for the specific alternative hypothesis of interest), then Replicability Index is possibly hugely overestimating power, and therefore hugely overestimating replicability of results.

I came up with the idea of framing this overestimation in terms of Type M error by defining something called a power inflation index. Here is how it works. For different "true" power levels, we repeatedly sample data, and compute observed power each time. Then, for each "true" power level, we can compute the ratio of the observed power to the true power in each case. The mean of this ratio is the power inflation index, and the 95% confidence interval around it gives us an indication (sorry Richard Morey! I know I am abusing the meaning of CI here and treating it like a credible interval!) of how badly we could overestimate power from a small sample study.

Here is the code for simulating and visualizing the power inflation index:

And here is the visualization:

What we see here is that if true power is as low as 0.05 (and we can never know that it is not since we never know the true effect size!), then using observed power can lead to gross overestimates by a factor of approximately 10! So, if Replicability Index reports an observed power of 0.75, what he might actually be looking at is an inflated estimate where true power is 0.08.

In summary, we can never know true power, and if we are estimating it using observed power conditional on true power being extremely low, we are likely to hugely overestimate power.

One way to test my claim is to actually try to replicate the studies that Replicability Index predicts has high replicability. My prediction is that his estimates will be wild overestimates and most studies will not replicate.

Postscript

A further thing that worries me about Replicability Index is his sloppy definitions of statistical terms. Here is how he defines power:

"Power is defined as the long-run probability of obtaining significant results in a series of exact replication studies. For example, 50% power means that a set of 100 studies is expected to produce 50 significant results and 50 non-significant results."

[Thanks to Karthik Durvasula for correcting my statement below!]

By not defining power of a test of a null hypothesis $H_0: \mu=k$, as the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis (as a function of different alternative $\mu$ such that $\mu\neq k$) when it is false, what this definition literally means is that if I sample from any distribution, including one where $\mu=0$, the probability of obtaining a significant result under repeated sampling is the power. Which of course is completely false.

Post-Post Script

Replicability Index points out in a tweet that his post-hoc power estimation corrects for inflation. But post-hoc power corrected for inflation requires knowledge of the true power, which is what we are trying to get at in the first place. How do you deflate "observed" power when you don't know what the true power is? Maybe I am missing something.

Indeed, the author of the Replicability Index has been using observed power to determine the replicability of journal articles. His observed power estimates are HUGE (in the range of 0.75) and seem totally implausible to me, given the fact that I can hardly ever replicate my studies.

This got me thinking: Gelman and Carlin have shown that when power is low, Type M error will be high. That is, the observed effects will tend to be highly exaggerated. The issue with Type M error is easy to visualize.

Suppose that a particular study has standard error 46, and sample size 37; this implies that standard deviation is $46\times \sqrt{37}= 279$. These are representative numbers from psycholinguistic studies. Suppose also that we know that the true effect (the absolute value, say on the millisecond scale for a reading study---thanks to Fred Hasselman) is D=15. Then, we can compute Type S and Type M errors for replications of this particular study by repeatedly sampling from the true distribution.

We can visualize the exaggerated effects under low power as follows (see below): On the x-axis you see the effect magnitudes, and on the y-axis is power. The red line is the power line of 0.20, which based on my own attempts at replicating my own studies (and mostly failing), I estimate to be an upper bound of the power of experiments in psycholinguistics (this is an upper bound, I think a more common value will be closer to 0.05). All those dots below the red line are exaggerated estimates in a low power situation, and if you were to use any of those points to estimate observed power, you would get a wildly optimistic power estimate which has no bearing with reality.

What does this fact about Type M error imply for Replicability Index's calculations? It implies that if power is in fact very low, and if journals are publishing larger-than-true effect sizes (and we know that they have an incentive to do so, because editors and reviewers mistakenly think that lower p-values, i.e., bigger absolute t-values, give stronger evidence for the specific alternative hypothesis of interest), then Replicability Index is possibly hugely overestimating power, and therefore hugely overestimating replicability of results.

I came up with the idea of framing this overestimation in terms of Type M error by defining something called a power inflation index. Here is how it works. For different "true" power levels, we repeatedly sample data, and compute observed power each time. Then, for each "true" power level, we can compute the ratio of the observed power to the true power in each case. The mean of this ratio is the power inflation index, and the 95% confidence interval around it gives us an indication (sorry Richard Morey! I know I am abusing the meaning of CI here and treating it like a credible interval!) of how badly we could overestimate power from a small sample study.

Here is the code for simulating and visualizing the power inflation index:

And here is the visualization:

What we see here is that if true power is as low as 0.05 (and we can never know that it is not since we never know the true effect size!), then using observed power can lead to gross overestimates by a factor of approximately 10! So, if Replicability Index reports an observed power of 0.75, what he might actually be looking at is an inflated estimate where true power is 0.08.

In summary, we can never know true power, and if we are estimating it using observed power conditional on true power being extremely low, we are likely to hugely overestimate power.

One way to test my claim is to actually try to replicate the studies that Replicability Index predicts has high replicability. My prediction is that his estimates will be wild overestimates and most studies will not replicate.

Postscript

A further thing that worries me about Replicability Index is his sloppy definitions of statistical terms. Here is how he defines power:

"Power is defined as the long-run probability of obtaining significant results in a series of exact replication studies. For example, 50% power means that a set of 100 studies is expected to produce 50 significant results and 50 non-significant results."

[Thanks to Karthik Durvasula for correcting my statement below!]

By not defining power of a test of a null hypothesis $H_0: \mu=k$, as the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis (as a function of different alternative $\mu$ such that $\mu\neq k$) when it is false, what this definition literally means is that if I sample from any distribution, including one where $\mu=0$, the probability of obtaining a significant result under repeated sampling is the power. Which of course is completely false.

Post-Post Script

Replicability Index points out in a tweet that his post-hoc power estimation corrects for inflation. But post-hoc power corrected for inflation requires knowledge of the true power, which is what we are trying to get at in the first place. How do you deflate "observed" power when you don't know what the true power is? Maybe I am missing something.

Monday, August 17, 2015

Some reflections on teaching frequentist statistics at ESSLLI 2015

I spent the last two weeks teaching frequentist and Bayesian statistics at the European Summer School in Logic, Language, and Information (ESSLLI) in Barcelona, at the beautiful and centrally located Pompeu Fabra University. The course web page for the first week is here, and the web page for the second course is here.

All materials for the first week are available on github, see here.

The frequentist course went well, but the Bayesian course was a bit unsatisfactory; perhaps my greater experience in teaching the frequentist stuff played a role (I have only taught Bayes for three years). I've been writing and rewriting my slides and notes for frequentist methods since 2002, and it is only now that I can present the basic ideas in five 90 minute lectures; with Bayes, the presentation is more involved and I need to plan more carefully, interspersing on-the-spot exercises to solidify ideas. I will comment on the Bayesian Data Analysis course in a subsequent post.

The first week (five 90 minute lectures) covered the basic concepts in frequentist methods. The audience was amazing; I wish I always had students like these in my classes. They were attentive, and anticipated each subsequent development. This was the typical ESSLLI crowd, and this is why teaching at ESSLLI is so satisfying. There were also several senior scientists in the class, so hopefully they will go back and correct the misunderstandings among their students about what all this Null Hypothesis Significance Testing stuff gives you (short answer: it answers *a* question very well, but it's the wrong question, nothing that is relevant to your research question).

I won't try to summarize my course, because the web page is online and you can also do exercises on datacamp to check your understanding of statistics (see here). You get immediate feedback on your attempts.

Stepping away from the technical details, I tried to make three broad points:

First, I spent a lot of time trying to clarify what a p-value is and isn't, focusing particularly on the issue of Type S and Type M errors, which Gelman and Carlin have discussed in their excellent paper.

Here is the way that I visualized the problems of Type S and Type M errors:

What we see here is repeated samples from a Normal distribution with true mean 15 and a typical standard deviation seen in psycholinguistic studies (see slide 42 of my slides for lecture2). The horizontal red line marks the 20% power line; most psycholinguistic studies fall below that line in terms of power. The dramatic consequence of this low power is the hugely exaggerated effects (which tend to get published in major journals because they also have low p-values) and the remarkable proportion of cases where the sample mean is on the wrong side of the true value 15. So, you are roughly equally likely to get a significant effect with a sample mean smaller to much smaller than the true mean, or larger and much larger than the true mean. With low power, regardless of whether you get a significant result or not, if power is low, and it is in most studies I see in journals, you are just farting in a puddle.

It is worth repeating this: once one considers Type S and Type M errors, even statistically significant results become irrelevant, if power is low. It seems like these ideas are forever going to be beyond the comprehension of researchers in linguistics and psychology, who are trained to make binary decisions based on p-values, weirdly accepting the null if p is greater than 0.05 and, just as weirdly, accepting their favored alternative if p is less than 0.05. The p-value is a truly interesting animal; it seems that a recent survey of some 400 Spanish psychologists found that, despite their being active in the field for quite a few years on average, they had close to zero understanding of what a p-value gives you. Editors of top journals in psychology routinely favor lower p-values, because they mistakenly think this makes "the result" more convincing; "the result" is the favored alternative. So even seasoned psychologists (and I won't even get started with linguists, because we are much, much worse), with decades of experience behind them, often have no idea what the p-value actually tells you.

A remarkable misunderstanding regarding p-values is the claim that it tells you whether the effect was "by chance". Here is an example from Replication Index's blog:

"The Test of Insufficient Variance (TIVA) shows that the variance in z-scores is less than 1, but the probability of this event to occur by chance is 10%, Var(z) = .63, Chi-square (df = 11) = 17.43, p = .096."

Here is another example from a self-published manuscript by Daniel Ezra Johnson:

"If we perform a likelihood-ratio test, comparing the model with gender to a null model with no predictors, we get a p-value of 0.0035. This implies that it is very unlikely that the observed gender difference is due to chance."

One might think that the above examples are not peer-reviewed, and that peer review would catch such mistakes. But even people explaining p-values in publications are unable to understand that this is completely false. An example is Keith Johnson's textbook, Quantitative Methods in Linguistics, which repeatedly talks about "reliable effects" and effects which are and are not due to chance. It is no wonder that the poor psychologist/linguist thinks, ok, if the p-value is telling me the probability that the effect is due to chance, and if the p-value is low, then the effect is not due to chance and the effect must be true. The mistake here is that the p-value is telling you the probability of the result being "due to chance" conditional on the null hypothesis being true. It's better to explain the p-value as the probability of getting the statistic (e.g., t-value) or something more extreme, under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. People seem to drop the italicized part and this starts to propagate the misunderstanding for future generations. To repeat, the p-value is a conditional probability, but most people interpret it as an unconditional probability because they drop the phrase "under the null hypothesis" and truncate the statement to be about effects being due to chance.

Another bizarre thing I have repeatedly seen is misinterpreting the p-value as Type I error. Type I error is fixed at a particular value (0.05) before you run the experiment, and is the probability of your incorrectly rejecting the null when it's true, under repeated sampling. The p-value is what you get from your single experiment and is the conditional probability of your getting the statistic you got or something more extreme, assuming that the null is true. Even this point is beyond comprehension for psychologists (and of course linguists). Here is a bunch of psychologists explaining in an article why a p=0.000 should not be reported as an exact value:

The p-value is the probability of committing a Type I error, eh? It is truly embarrassing that people who are teaching this stuff have distorted the meaning of the p-value so drastically and just keep propagating the error. I should mention though that this paper I am citing appeared in Frontiers, which I am beginning to question as a worthwhile publication venue. Who did the peer review on this paper and why did they not catch this basic mistake?

Even Fisher (p. 16 of The Design of Experiments, Second Edition, 1937) didn't buy the p-value; he is advocating for replicability as the real decisive tool:

"It is usual and convenient for experimenters to take-5 per cent. as a standard level of significance, in the sense that they are prepared to ignore all results which fail to reach this standard, and, by this means, to eliminate from further discussion the greater part of the fluctuations which chance causes have introduced into their experimental results. No such selection can eliminate the whole of the possible effects of chance. coincidence, and if we accept this convenient convention, and agree that an event which would occur by chance only once in 70 trials is decidedly" significant," in the statistical sense, we thereby admit that no isolated experiment, however significant in itself, can suffice for the experimental demonstration of any natural phenomenon; for the "one chance in a million" will undoubtedly occur, with no less and no more than its appropriate frequency, however surprised we may be that it should occur to us. In order to assert that a natural phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable we need, not an isolated record, but a reliable method of procedure. In relation to the test of significance, we may say that a phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable when we know how to conduct an experiment which will rarely fail to give us a statistically significant result."

Second, I tried to clarify what a 95% confidence interval is and isn't. At least a couple of students had a hard time accepting that the 95% CI refers to the procedure and not that the true $\mu$ lies within one specific interval with probability 0.95, until I pointed out that $\mu$ is just a point value and doesn't have a probability distribution associated with it. Morey and Wagenmakers and Rouder et al have been shouting themselves hoarse about confidence intervals, and how many people don't understand them, also see this paper. Ironically, psychologists have responded to these complaints through various media, but even this response only showcases how psychologists have only a partial and misconstrued understanding of confidence intervals. I feel that part of the problem is that scientists hate to back off from a position they have taken, and so they tend to hunker down and defend defend defend their position. From the perspective of a statistician who understands both Bayes and frequentist positions, the conclusion would have to be that Morey et al are right, but for large sample sizes, the difference between a credible interval and a confidence interval (I mean the actual values that you get for the lower and upper bound) are negligible. You can see examples in our recently ArXiv'd paper.

Third, I tried to explain that there is a cultural difference between statisticians on the one hand and (most) psychologists and almost all psychologist, linguists, etc. on the other. For the latter group (with the obvious exception of people using Bayesian methods for data analysis), the whole point of fitting a statistical model is to do a hypothesis test, i.e., to get a p-value out of it. They simply do not care what the assumptions and internal moving parts of a t-test or a linear mixed model are. I know lots of users of lmer who are focused on one and only one thing: is my effect significant? I have repeatedly seen experienced experimenters in linguistics simply ignoring the independence assumption of data points when doing a paired t-test; people often do paired t-tests on unaggregated data, with multiple rows of data points for each subject (for example). This leads to spurious significance effects, which they happily and unquestioningly accept because that was the whole goal of the exercise. I show some examples in my lecture2 slides (slide 70).

It's not just linguists, you can see the consequences of ignoring the independence assumption in this reanalysis of the infamous study on how future tense marking in language supposedly influences economic decisions. Once the dependencies between languages are taken into account, the conclusion that Chen originally drew doesn't really hold up much:

" When applying the strictest tests for relatedness, and when data is not aggregated across individuals, the correlation is not significant."

Similarly, Amy Cuddy et al's study on how power posing increases testosterone levels also got published only because the p value just scraped in below 0.05 at 0.045 or so. You can see in their figure 3 reporting the testosterone increase

that their confidence intervals are huge (this is probably why they report standard errors, it wouldn't look so impressive if they had reported CIs). All they needed to show to make their point was to get the p-value below 0.05. The practical relevance of a 12 picogram/ml increase in testosterone is left unaddressed. Another recent example from Psychological Science, which seems to publish studies that might attract attention in the popular press, is this study on how ovulating women wear red. This study is a follow up on the notorious Psychological Science study by Beall and Tracy. In my opinion, the Beall and Tracy study reports a bogus result because they claim that women wear red or pink when ovulating, but when I reanalyzed their data I found that the effect was driven by pink alone. Here is my GLM fit for red or pink, red only and pink only. You can see that the "statistically significant" effect is driven entirely by pink, making the title of their paper (Women Are More Likely to Wear Red or Pink at Peak Fertility) true only if you allow the exclusive-or reading of the disjunction:

The new study by Eisenbruch et al reports a statistically significant effect on this red-pink issue, but now it's only about red:

"A mixed regression model confirmed that, within subjects, the odds of wearing red were higher during the estimated fertile window than on other cycle days, b = 0.93, p = .040, odds ratio (OR) = 2.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [1.04, 6.14]. The 2.53 odds ratio indicates that the odds of wearing a red top were about 2.5 times higher inside the fertile window, but there was a wide confidence interval."

To their credit, they note that their confidence interval is huge, and essentially includes 1. But since the p-value is below 0.05 this result is considered evidence for the "red hypothesis". It may well be that women who are ovulating wear red; I have no idea and have no stake in the issue. Certainly, I am not about to start looking at women wearing red as potential sexual partners (quite independent from the fact that my wife would probably kill me if I did). But it would be nice if people would try to do high powered studies, and report a replication in the same study they publish. Luckily nobody will die if these studies report mistaken results, but the same mistakes are happening in medicine, where people will die as a result of incorrect conclusions being drawn.

All these examples show why the focus on p-values is so damaging for answering research questions.

Not surprisingly, for the statistician, the main point of fitting a model (even in a confirmatory factorial analysis) is not to derive a p-value from it; in fact, for many statisticians the p-value may not even rise to consciousness. The main point of fitting a model is to define a process which describes, in the most economical way possible, how the data were generated. If the data don't allow you to estimate some of the parameters, then, for a statistician it is completely reasonable to back off to defining a simpler generative process.

This is what Gelman and Hill also explain in their 2007 book (italics mine). Note that they are talking about fitting Bayesian linear mixed models (in which parameters like correlations can be backed off to 0 by using appropriate priors; see the Stan code using lkj priors here), not frequentist models like lmer. Also, Gelman would never, ever compute a p-value.

Gelman and Hill 2007, p. 549:

For the statistician, simplicity of expression and understandability of the model (in the Gelman and Hill sense of being able to derive sensible posterior (predictive) distributions) are of paramount importance. For the psychologist and linguist (and other areas), what matters is whether the result is statistically significant. The more vigorously you can reject the null, the more excited you get, and the language provided for this ("highly significant") also gives the illusion that we have found out something important (=significant).

This seems to be a fundamental disconnect between statisticians, and end-users who just want their p-value. A further source of the disconnect is that linguists and psychologists etc. look for cookbook methods, what a statistician I know once derisively called a "one and done" approach. This leads to blind data fitting: load data, run single line of code, publish result. No question ever arises about whether the model even makes sense. In a way this is understandable; it would be great if there was a one-shot solution to fitting, e.g., linear mixed models. It would simplify life so much, and one wouldn't need to spend years studying statistics before one can do science. However, the same scientists who balk at studying statistics will willingly spend time studying their field of expertise. No mainstream (by which I mean Chomskyan) syntactician is going to ever use commercial software to print out his syntactic derivation without knowing anything about the syntactic theory. Yet this is exactly what these same people expect from statistical software, to get an answer without having any understanding of the underlying statistical machinery.

The bottom line that I tried to convey in my course was: forget about the p-value (except to soothe the reviewer and editor and to build your career), focus on doing high powered studies, check model assumptions, fit appropriate models, replicate your findings, and publish against your own pet theories. Understanding what all these words means requires some study, and we should not shy away from making that effort.

PS I am open to being corrected---like everyone else, I am prone to making mistakes. Please post corrections, but with evidence, in the comments section. I moderate the comments because some people post spam there, but I will allow all non-spam comments.

PPS The teaching evaluation for this course just came in from ESSLLI; here it is. I believe 5.0 is a perfect score.

All materials for the first week are available on github, see here.

The frequentist course went well, but the Bayesian course was a bit unsatisfactory; perhaps my greater experience in teaching the frequentist stuff played a role (I have only taught Bayes for three years). I've been writing and rewriting my slides and notes for frequentist methods since 2002, and it is only now that I can present the basic ideas in five 90 minute lectures; with Bayes, the presentation is more involved and I need to plan more carefully, interspersing on-the-spot exercises to solidify ideas. I will comment on the Bayesian Data Analysis course in a subsequent post.

The first week (five 90 minute lectures) covered the basic concepts in frequentist methods. The audience was amazing; I wish I always had students like these in my classes. They were attentive, and anticipated each subsequent development. This was the typical ESSLLI crowd, and this is why teaching at ESSLLI is so satisfying. There were also several senior scientists in the class, so hopefully they will go back and correct the misunderstandings among their students about what all this Null Hypothesis Significance Testing stuff gives you (short answer: it answers *a* question very well, but it's the wrong question, nothing that is relevant to your research question).

I won't try to summarize my course, because the web page is online and you can also do exercises on datacamp to check your understanding of statistics (see here). You get immediate feedback on your attempts.

Stepping away from the technical details, I tried to make three broad points:

First, I spent a lot of time trying to clarify what a p-value is and isn't, focusing particularly on the issue of Type S and Type M errors, which Gelman and Carlin have discussed in their excellent paper.

Here is the way that I visualized the problems of Type S and Type M errors:

What we see here is repeated samples from a Normal distribution with true mean 15 and a typical standard deviation seen in psycholinguistic studies (see slide 42 of my slides for lecture2). The horizontal red line marks the 20% power line; most psycholinguistic studies fall below that line in terms of power. The dramatic consequence of this low power is the hugely exaggerated effects (which tend to get published in major journals because they also have low p-values) and the remarkable proportion of cases where the sample mean is on the wrong side of the true value 15. So, you are roughly equally likely to get a significant effect with a sample mean smaller to much smaller than the true mean, or larger and much larger than the true mean. With low power, regardless of whether you get a significant result or not, if power is low, and it is in most studies I see in journals, you are just farting in a puddle.

It is worth repeating this: once one considers Type S and Type M errors, even statistically significant results become irrelevant, if power is low. It seems like these ideas are forever going to be beyond the comprehension of researchers in linguistics and psychology, who are trained to make binary decisions based on p-values, weirdly accepting the null if p is greater than 0.05 and, just as weirdly, accepting their favored alternative if p is less than 0.05. The p-value is a truly interesting animal; it seems that a recent survey of some 400 Spanish psychologists found that, despite their being active in the field for quite a few years on average, they had close to zero understanding of what a p-value gives you. Editors of top journals in psychology routinely favor lower p-values, because they mistakenly think this makes "the result" more convincing; "the result" is the favored alternative. So even seasoned psychologists (and I won't even get started with linguists, because we are much, much worse), with decades of experience behind them, often have no idea what the p-value actually tells you.

A remarkable misunderstanding regarding p-values is the claim that it tells you whether the effect was "by chance". Here is an example from Replication Index's blog:

"The Test of Insufficient Variance (TIVA) shows that the variance in z-scores is less than 1, but the probability of this event to occur by chance is 10%, Var(z) = .63, Chi-square (df = 11) = 17.43, p = .096."

Here is another example from a self-published manuscript by Daniel Ezra Johnson:

"If we perform a likelihood-ratio test, comparing the model with gender to a null model with no predictors, we get a p-value of 0.0035. This implies that it is very unlikely that the observed gender difference is due to chance."

One might think that the above examples are not peer-reviewed, and that peer review would catch such mistakes. But even people explaining p-values in publications are unable to understand that this is completely false. An example is Keith Johnson's textbook, Quantitative Methods in Linguistics, which repeatedly talks about "reliable effects" and effects which are and are not due to chance. It is no wonder that the poor psychologist/linguist thinks, ok, if the p-value is telling me the probability that the effect is due to chance, and if the p-value is low, then the effect is not due to chance and the effect must be true. The mistake here is that the p-value is telling you the probability of the result being "due to chance" conditional on the null hypothesis being true. It's better to explain the p-value as the probability of getting the statistic (e.g., t-value) or something more extreme, under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. People seem to drop the italicized part and this starts to propagate the misunderstanding for future generations. To repeat, the p-value is a conditional probability, but most people interpret it as an unconditional probability because they drop the phrase "under the null hypothesis" and truncate the statement to be about effects being due to chance.

Another bizarre thing I have repeatedly seen is misinterpreting the p-value as Type I error. Type I error is fixed at a particular value (0.05) before you run the experiment, and is the probability of your incorrectly rejecting the null when it's true, under repeated sampling. The p-value is what you get from your single experiment and is the conditional probability of your getting the statistic you got or something more extreme, assuming that the null is true. Even this point is beyond comprehension for psychologists (and of course linguists). Here is a bunch of psychologists explaining in an article why a p=0.000 should not be reported as an exact value:

"p = 0.000. Even though this statistical expression,

used in over 97,000 manuscripts according to Google Scholar,

makes regular cameo appearances in our computer printouts, we

should assiduously avoid inserting it in our Results sections. This

expression implies erroneously that there is a zero probability

that the investigators have committed a Type I error, that is, a

false rejection of a true null hypothesis (Streiner, 2007). That

conclusion is logically absurd, because unless one has examined

essentially the entire population, there is always some chance

of a Type I error, no matter how meager. Needless to say, the

expression “p < 0.000” is even worse, as the probability of

committing a Type I error cannot be less than zero. Authors

whose computer printouts yield significance levels of p = 0.000

should instead express these levels out to a large number of

decimal places, or at least indicate that the probability level is

below a given value, such as p < 0.01 or p < 0.001."

The p-value is the probability of committing a Type I error, eh? It is truly embarrassing that people who are teaching this stuff have distorted the meaning of the p-value so drastically and just keep propagating the error. I should mention though that this paper I am citing appeared in Frontiers, which I am beginning to question as a worthwhile publication venue. Who did the peer review on this paper and why did they not catch this basic mistake?

Even Fisher (p. 16 of The Design of Experiments, Second Edition, 1937) didn't buy the p-value; he is advocating for replicability as the real decisive tool:

"It is usual and convenient for experimenters to take-5 per cent. as a standard level of significance, in the sense that they are prepared to ignore all results which fail to reach this standard, and, by this means, to eliminate from further discussion the greater part of the fluctuations which chance causes have introduced into their experimental results. No such selection can eliminate the whole of the possible effects of chance. coincidence, and if we accept this convenient convention, and agree that an event which would occur by chance only once in 70 trials is decidedly" significant," in the statistical sense, we thereby admit that no isolated experiment, however significant in itself, can suffice for the experimental demonstration of any natural phenomenon; for the "one chance in a million" will undoubtedly occur, with no less and no more than its appropriate frequency, however surprised we may be that it should occur to us. In order to assert that a natural phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable we need, not an isolated record, but a reliable method of procedure. In relation to the test of significance, we may say that a phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable when we know how to conduct an experiment which will rarely fail to give us a statistically significant result."

Second, I tried to clarify what a 95% confidence interval is and isn't. At least a couple of students had a hard time accepting that the 95% CI refers to the procedure and not that the true $\mu$ lies within one specific interval with probability 0.95, until I pointed out that $\mu$ is just a point value and doesn't have a probability distribution associated with it. Morey and Wagenmakers and Rouder et al have been shouting themselves hoarse about confidence intervals, and how many people don't understand them, also see this paper. Ironically, psychologists have responded to these complaints through various media, but even this response only showcases how psychologists have only a partial and misconstrued understanding of confidence intervals. I feel that part of the problem is that scientists hate to back off from a position they have taken, and so they tend to hunker down and defend defend defend their position. From the perspective of a statistician who understands both Bayes and frequentist positions, the conclusion would have to be that Morey et al are right, but for large sample sizes, the difference between a credible interval and a confidence interval (I mean the actual values that you get for the lower and upper bound) are negligible. You can see examples in our recently ArXiv'd paper.

Third, I tried to explain that there is a cultural difference between statisticians on the one hand and (most) psychologists and almost all psychologist, linguists, etc. on the other. For the latter group (with the obvious exception of people using Bayesian methods for data analysis), the whole point of fitting a statistical model is to do a hypothesis test, i.e., to get a p-value out of it. They simply do not care what the assumptions and internal moving parts of a t-test or a linear mixed model are. I know lots of users of lmer who are focused on one and only one thing: is my effect significant? I have repeatedly seen experienced experimenters in linguistics simply ignoring the independence assumption of data points when doing a paired t-test; people often do paired t-tests on unaggregated data, with multiple rows of data points for each subject (for example). This leads to spurious significance effects, which they happily and unquestioningly accept because that was the whole goal of the exercise. I show some examples in my lecture2 slides (slide 70).

It's not just linguists, you can see the consequences of ignoring the independence assumption in this reanalysis of the infamous study on how future tense marking in language supposedly influences economic decisions. Once the dependencies between languages are taken into account, the conclusion that Chen originally drew doesn't really hold up much:

" When applying the strictest tests for relatedness, and when data is not aggregated across individuals, the correlation is not significant."

Similarly, Amy Cuddy et al's study on how power posing increases testosterone levels also got published only because the p value just scraped in below 0.05 at 0.045 or so. You can see in their figure 3 reporting the testosterone increase

that their confidence intervals are huge (this is probably why they report standard errors, it wouldn't look so impressive if they had reported CIs). All they needed to show to make their point was to get the p-value below 0.05. The practical relevance of a 12 picogram/ml increase in testosterone is left unaddressed. Another recent example from Psychological Science, which seems to publish studies that might attract attention in the popular press, is this study on how ovulating women wear red. This study is a follow up on the notorious Psychological Science study by Beall and Tracy. In my opinion, the Beall and Tracy study reports a bogus result because they claim that women wear red or pink when ovulating, but when I reanalyzed their data I found that the effect was driven by pink alone. Here is my GLM fit for red or pink, red only and pink only. You can see that the "statistically significant" effect is driven entirely by pink, making the title of their paper (Women Are More Likely to Wear Red or Pink at Peak Fertility) true only if you allow the exclusive-or reading of the disjunction:

The new study by Eisenbruch et al reports a statistically significant effect on this red-pink issue, but now it's only about red:

"A mixed regression model confirmed that, within subjects, the odds of wearing red were higher during the estimated fertile window than on other cycle days, b = 0.93, p = .040, odds ratio (OR) = 2.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [1.04, 6.14]. The 2.53 odds ratio indicates that the odds of wearing a red top were about 2.5 times higher inside the fertile window, but there was a wide confidence interval."

To their credit, they note that their confidence interval is huge, and essentially includes 1. But since the p-value is below 0.05 this result is considered evidence for the "red hypothesis". It may well be that women who are ovulating wear red; I have no idea and have no stake in the issue. Certainly, I am not about to start looking at women wearing red as potential sexual partners (quite independent from the fact that my wife would probably kill me if I did). But it would be nice if people would try to do high powered studies, and report a replication in the same study they publish. Luckily nobody will die if these studies report mistaken results, but the same mistakes are happening in medicine, where people will die as a result of incorrect conclusions being drawn.

All these examples show why the focus on p-values is so damaging for answering research questions.

Not surprisingly, for the statistician, the main point of fitting a model (even in a confirmatory factorial analysis) is not to derive a p-value from it; in fact, for many statisticians the p-value may not even rise to consciousness. The main point of fitting a model is to define a process which describes, in the most economical way possible, how the data were generated. If the data don't allow you to estimate some of the parameters, then, for a statistician it is completely reasonable to back off to defining a simpler generative process.

This is what Gelman and Hill also explain in their 2007 book (italics mine). Note that they are talking about fitting Bayesian linear mixed models (in which parameters like correlations can be backed off to 0 by using appropriate priors; see the Stan code using lkj priors here), not frequentist models like lmer. Also, Gelman would never, ever compute a p-value.

Gelman and Hill 2007, p. 549:

"Don’t get hung up on whether a coefficient “should” vary by group. Just allow it

to vary in the model, and then, if the estimated scale of variation is small (as with

the varying slopes for the radon model in Section 13.1), maybe you can ignore it if

that would be more convenient.

Practical concerns sometimes limit the feasible complexity of a model—for example, we might fit a varying-intercept model first, then allow slopes to vary, then add group-level predictors, and so forth. Generally, however, it is only the difficulties of fitting and, especially, understanding the models that keeps us from adding even more complexity, more varying coefficients, and more interactions."

Practical concerns sometimes limit the feasible complexity of a model—for example, we might fit a varying-intercept model first, then allow slopes to vary, then add group-level predictors, and so forth. Generally, however, it is only the difficulties of fitting and, especially, understanding the models that keeps us from adding even more complexity, more varying coefficients, and more interactions."

For the statistician, simplicity of expression and understandability of the model (in the Gelman and Hill sense of being able to derive sensible posterior (predictive) distributions) are of paramount importance. For the psychologist and linguist (and other areas), what matters is whether the result is statistically significant. The more vigorously you can reject the null, the more excited you get, and the language provided for this ("highly significant") also gives the illusion that we have found out something important (=significant).

This seems to be a fundamental disconnect between statisticians, and end-users who just want their p-value. A further source of the disconnect is that linguists and psychologists etc. look for cookbook methods, what a statistician I know once derisively called a "one and done" approach. This leads to blind data fitting: load data, run single line of code, publish result. No question ever arises about whether the model even makes sense. In a way this is understandable; it would be great if there was a one-shot solution to fitting, e.g., linear mixed models. It would simplify life so much, and one wouldn't need to spend years studying statistics before one can do science. However, the same scientists who balk at studying statistics will willingly spend time studying their field of expertise. No mainstream (by which I mean Chomskyan) syntactician is going to ever use commercial software to print out his syntactic derivation without knowing anything about the syntactic theory. Yet this is exactly what these same people expect from statistical software, to get an answer without having any understanding of the underlying statistical machinery.

The bottom line that I tried to convey in my course was: forget about the p-value (except to soothe the reviewer and editor and to build your career), focus on doing high powered studies, check model assumptions, fit appropriate models, replicate your findings, and publish against your own pet theories. Understanding what all these words means requires some study, and we should not shy away from making that effort.

PS I am open to being corrected---like everyone else, I am prone to making mistakes. Please post corrections, but with evidence, in the comments section. I moderate the comments because some people post spam there, but I will allow all non-spam comments.

PPS The teaching evaluation for this course just came in from ESSLLI; here it is. I believe 5.0 is a perfect score.

Statistical methods for linguistic research: Foundational Ideas (Vasishth)

| Lecturer1 | 4.9 |

| Did the course content correspond to what was proposed? | 4.9 |

| Course notes | 4.6 |

| Session attendance | 4.4 |

(19 respondents)

- Very good course.

- The lecturer was simply great. He has made hard concepts really easy to understand. He also has been able to keep the class interested. A real pity to miss the last lecture !!

- The only reason that this wasn't the best statistics course is that I had a great lecturer at my university on this. Very entertaining, informative, and correct lecture, I can't think of anything the lecturer could do better.

- Informative, deep and witty. Simply awesome.

- Professor Shravan Vasishth was hands down the best lecturer at ESSLLI 2015. I envy the people who actually get to learn from him for a whole semester instead of just a week or two. The course was challenging for someone with not much background in statistics, but Professor Vasishth provided a bunch of additional material. He's the best!

- Great course, very detailed explanations and many visual examples of some statistical phenomena. However, it would be better to include more information on regression models, especially with effects (model quality evaluation, etc) and more examples of researches from linguistic field.

- It was an extremely useful course presented by one of the best lecturers I've ever met. Thank you!

- Amazing course. Who would have thought that statistics could be so interesting and engaging? Kudos to lecturer Shravan Vasishth who managed to condense so much information into only 5 sessions, who managed to filter out only the most relevant things that will be applicable and indeed used by everyone who attendet the course and who managed to show the usefulness of the material. A great lecturer who never went on until everything was cleared up and made even the most daunting of statistical concepts seem surmountable. The only thing I'm sorry for is not having the opportunity to take his regular, semester-long statistics course so I can enjoy a more in depth look at the material and let everything settle properly. Five stars, would take again.

- Absolutely great!!

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Getting a statistics education: Review of the MSc in Statistics (Sheffield)

[This post was written between Sept 2012 and Feb 2015. I will post an update in Sept. 2015]

[This post was written between Sept 2012 and Feb 2015. I will post an update in Sept. 2015] Last edit: June 27, 2015

Final edit: Nov 3, 2015 (added MSc thesis grade)

Some background:

I started using statistics for my research sometime in 1999 or 2000. I was a student at Ohio State, Linguistics, and I had just gotten interested in psycholinguistics. I knew almost nothing about statistics at that time. I did one Intro to Stats course in my department with Mike Broe (4 weeks), and that was it. In 1999 I developed repetitive strain injury, partly from using Excel and SPSS, and started googling for better statistical software. Someone pointed me to |stat, but eventually I found R. That was a transformative moment.

The next stage in my education came in 2000, when I decided to go to the Statistical Consulting department at OSU and showed them my repeated measure ANOVA analyses. The response I got was: why are you fitting ANOVAs? You need linear mixed models. The statisticians showed me what I had to do code-wise, and I went ahead and finished my dissertation work using the nlme package. The Pinheiro and Bates book had just come out then and I got myself a copy, understanding almost nothing in the book beyond the first few chapters.

After that, I published a few more papers on sentence processing using nlme and then lmer, and in 2011 I co-wrote a book with Mike Broe (the basic template of the book was based on his lecture notes at OSU, he had used Mathematica or something like that, but I used R and expanded on his excellent simulation-based approach). This book revealed the incompleteness of my understanding, as spelled out in the scathing (and well-deserved) critique by Christian Robert. Even before this review came out, I had already realized in early 2011 that I didn't really understand what I was doing. My sabbatical was coming up in winter 2011, and I enrolled for the graduate certificate in statistics at Sheffield to get a better understanding of statistical theory. Here is my review of the distance-based graduate certificate in statistics taught at Sheffield.

At the end of that graduate certificate, I felt that I still didn't really understand much that was of practical relevance to my life as a researcher. That led me to do the MSc in Statistics at Sheffield, which I have been doing over three years (2012-15). This is a review of the MSc program.

Short version of this review: The three year distance MSc program at Sheffield is outstanding. I highly recommend it to anyone wanting to acquire a good, basic understanding of statistical theory and inference. You can alternatively do the course over two years (probably impossible or very hard if you are also working full time, like me), or over one year full time (I don't know how people can do the degree in one year and still enjoy it). Be prepared to work hard and to find your own answers.

Long version:

Cost: For EU citizens, the three-year part time program costs about 2000 British pounds a year, not including the travel costs to get to Sheffield for the annual exams and presentations. For non-EU citizens, it's about 5000 pounds a year, still cheaper than most US programs.

Summary notes of the MSc program: I made summary notes for the exams during the three years. These are still very much in progress and are available from:

https://github.com/vasishth/MScStatisticsNotes

The courses I found most interesting and practically useful for my own research were Linear Modelling, Inference (Bayesian Statistics and Computational Inference), Medical Statistics, and Dependent data (Multivariate Analysis).

Course structure: Over three years, one does two courses each year, plus a dissertation. One has to commit about 15-20 hours a week in the 3-year program, although I think I did not do that much work, more like 12 hours a week on average (I had a lot of other work to do and just didn't have enough time to devote to statistics). There are four 3 hour sort-of open book exams that one has to go to Sheffield for, plus a group oral presentation, a simulated consultation, and project submissions. Every course has regular assignments/projects, all are graded but only a subset count for the final exam (15% of the final grade). The minimum you have to get to pass is 50%.

The MSc program is taught to residential students and to distance students in parallel: the residentials are there in Sheffield, attending lectures etc. The distance students follow the course over a mailing list. So, someone like me, who's doing the course over three years, is going to overlap with three batches of the MSc residential students. This has the effect that one has no classmates one knows, except maybe others who are doing the same three-year sequence with you.

The exams, which are the most stressful part of the program, are open book in that one can bring lecture notes and one's own but no textbooks. However, the exams are designed in such a way that if you don't already know the material inside out, there is almost no point in taking lecture notes in with you---there won't be enough time to look up the notes. I did take the official lecture notes with me for the first three exams, but I never once opened them. Instead, I only relied on my own summary sheets. Also, the exams are designed so that most people can't finish the required questions (any 5 out of 6) in the three hours. At least I never managed to finish all the questions to my satisfaction in any exam.

The first year (2012-13)

The first year courses were 6002 (Stats Lab) and 6003 (Linear Modelling). There was a project-based assessment for the first, and a 3 hour exam for the second.

6002 (Stats Lab): most of the course was about learning R, which anyone who had done the grad certificate did not need. It was only in the last weeks that things got interesting, with optimization. I didn't like the notes on optimization and MLE much, though. There wasn't enough detail, and I had to go searching in books and on the internet to find comprehensive discussions. Here I would recommend Ben Bolker's chapters 6-8, which are on his web page, complete with .Rnw files. Also, I just found a neat looking book (not read yet) which I wish I had had in 2012: Modern Optimization with R.

Overall the Stats Lab course had the feel of an intro to R, which is what it should have been called. It should have been possible to test out of such a course---I did not need to read the first 12 of 13 chapters over 9 months, I could have done it in a week or less, I'm sure that's true for those of my classmates who did the graduate certificate. However, I do see the point of the course for non-R users. I guess this is the perennial problem of teaching; students come in with different levels, you have to cater to the lowest common denominator. Also, the introduction to R is pretty dated and needs a major overhaul. Much has happened since Hadley Wickham arrived on the scene, and it's a shame not to use his packages. Finally, the absence of literate programming tools was surprising to me. I expected it to be a standard operating procedure in statistics to use Sweave or the like.

6003 (Linear Modelling): this course was absolutely amazing. The lecture notes were very well-written and very detailed (with some exceptions, noted below). Linear mixed models didn't get a particularly detailed treatment; I would have preferred a matrix presentation of LMM theory, and would have liked to learn how to implement these models myself.

Some problems I faced in year 1:

One issue in the course was the slow return of corrected assignments. By the time the assignment comes back graded (well, we just get general feedback and a grade), you've forgotten the details. Another strange aspect is that the grades for assignments were sometimes sent by regular air-mail. This was surprising in an online course.

One frustrating aspect of the courses was that a number of statements were made without any justification, proof, or further explanation. Example: "In R the default choice is the corner-point constraints given above, but in SPlus the default is the Helmert form, which is more convenient computationally, though more difficult to interpret." Wow, I want to know more! But this point is never discussed again. One consequence is a feeling that one must simply take certain facts as given (or work it out yourself). I think it would have been helpful to point the interested student to a reference.

The responses to questions on the mailing list are sometimes slow to come. Answers to questions asked online sometimes didn't really address the question, and one was left in the same state of uncertainty as earlier (a familiar feeling when you talk to a statistician!).

Where the graduate certificate shone was in the excruciatingly detailed feedback; this was where I learnt the most in that course. By contrast, the feedback to some of the assignments was pretty sketchy. I never really knew what a perfect solution would have looked like.

Of course, I can see why all this happens: professors are busy, and not always able to respond quickly to questions. I myself am sometimes just as slow to respond as a teacher; I guess I need to work on that aspect of my own teaching.

My final marks in these first-year courses were 63 per cent in each course.

The second year (2013-14)

The second year courses were 6001 (Data Analysis) and 6004 (Inference: Bayesian Statistics and Computational Inference). There was a project-based assessment for the first, and a 3 hour exam for the second.

In Data Analysis we did several projects which simulated real-life consulting, or involved doing actual experiments (e.g., building aeroplanes). There was one project where one had to choose a news media article about a piece of scientific work, and then compare it with the actual scientific work. The consulting project didn't work so well for me, because we were teamed up in fives and we didn't know each other. It was very hard to coordinate a project when all your colleagues are unknown to you, and email is the only way to communicate.

For the news media article, I chose the article Gelman attacked on his blog, about women wearing red to signal sexual availability. It was interesting because the claims in the Psych Science didn't really pan out. I reanalyzed the original data, and found that the effect was driven by pink, not red; the authors had recoded red and pink as red or pink, presumably in order to make the claim that women wear reddish hues. It's hard to believe that this was not a post-hoc step after seeing the data (although I think the authors claim it was not---I suppose it's possible that it wasn't); after all, if they had originally intended to treat red and pink as one unit color type, then why did they have two columns, one for red and one for pink?

The Data Analysis course was definitely not challenging; it was rather below the level of data analysis I have to do in my own research. However, I was thankful not to be overloaded in this course because the Bayesian analysis course took up all my energy in my second year.

The course on Bayesian statistics was a whole other animal. I read a lot of books that were not assigned as required readings (mostly, Gelman et al's BDA3, and Lunn et al, but also Lynch's excellent textbook). I did all the three exercises that were assigned (these are graded but do not count for the final grade). My scores were 20/20, 22/30, 23/30. I never really understood what exactly led to those points being lost; not much detailed explanation was provided. One doesn't know how many marks one loses for making a figure too small, for example (I was following Gelman's example of showing lots of figures, which requires making them smaller, but evidently this was frowned upon). As is typical for this degree program, the grading is pretty harsh and tight-lipped (the harsh grading is not a bad thing; but the lack of information on what to improve in the answer was frustrating).

The Bayesian lecture notes could be improved. They seem to have a disjointed feel; perhaps they were written by different people. The Bayesian lecture notes were very different than, say, the linear modeling notes, which really drilled the student on practical details of model fitting. In the Bayesian course, there were sudden transitions to topics that fizzled out quickly and were never resurrected. An example is decision theory; one section starts out defining some basic concepts, and then quickly ends. Inference and decision theory was never discussed. There were sections that were in the notes but not needed for the exams; for an MSc level program I would have wanted to read that material (and did). I had some questions on these non-examinable sections, but never could get an answer, which was pretty frustrating.